Final Fantasy X-2: Life is Such a Changing Art

It might seem impossible to remember, but at one point, revisiting the world of a previous Final Fantasy was unprecedented. (Well, almost unprecedented.) When Square first started dropping unsubtle hints that it might create a follow-up to Final Fantasy X, fans were skeptical. What about Final Fantasy’s long-standing tradition of creating a new world in each and every game?

But while Final Fantasy X-2 might look like the harbinger of Square’s later disasters, it’s unfair to lump it in the same category as Dirge of Cerberus or The After Years. Not only does it stand as a quality title in its own right, it enjoys a particularly unique relationship with its predecessor. What’s remarkable about X-2 is that it’s less of an expansion pack–the same thing, just bigger and better–and more of a mirror image. Instead of trying to duplicate Final Fantasy X, FFX-2 complements it; by making the opposite thematic and gameplay choices, it becomes part of a bigger picture that achieves more than either game could alone.

The Road Goes Ever On

The two games might be set in the same fictional world, but they approach it from different, complementary perspectives. FFX’s frame story has Tidus narrating events to Yuna; X-2’s has Yuna narrating them to an unseen Tidus, shifting the viewpoint character from a man who’s the ultimate outsider in Spira to the woman who became its greatest hero. In FFX, the ultimate goal was to destroy Sin, an ancient magical creature; FFX-2 unveils the new threat of Vegnagun, a technological weapon that Sin was created to battle. And, of course, the games’ themes and moods couldn’t be more distinct: FFX’s generally bleak quest to finally liberate Spira from the death and destruction of Sin at great personal cost paves the way for the new optimism and opportunity of a post-Sin era.

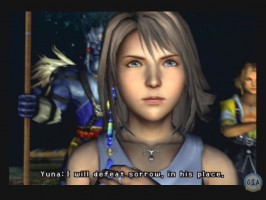

And yet, it’s not just the stories that dovetail together. In the early 2000s, the evolution of the console RPG was at a crossroads, and the two games have vastly different perspectives towards the genre’s maturation. FFX inherits the 90s’ progress towards more and more complex narratives–introducing voice acting and a narrative framing device to the Final Fantasy series–and adheres to the idea of an RPG as extremely linear, polished guided tour. Yuna’s pilgrimage to the holy city of Zanarkand traverses a single, well-trodden road with plenty of setpieces but few opportunities for detours. New game mechanics are doled out gradually. For most of the game, there are few sidequests–who has time for frivolities when Sin must be stopped?–and no back-tracking. It’s not until Yuna’s pivotal decision to reject the cycle of the Final Summoning and to truly fight for Spira’s freedom that the game finally opens up and allows the player to travel anywhere and do anything. It’s easy to fault this linear march as the prologue to today’s increasingly corridor-driven AAA titles, but in this case, the well-defined path is a natural fit for the game’s universe and events.

Where FFX emulates the structure of an epic fantasy novel, FFX-2 functions more like a collection of short stories. When the saga picks up two years later, Sin is long gone, and the citizens of Spira are trying to figure out what to do with their new-found freedom. Yuna, summoner no more, is handed an airship less than an hour into the game and almost immediately has the freedom to go anywhere and do anything in no predefined order. The unrestrained world means it’s sometimes possible to miss out on some events or rare items, but, well, that’s the price of freedom. Befitting Spira’s new search for meaning, only a fraction of the player’s time is spent pursuing the main Vegnagun arc; the great majority is spent questing around Spira in side missions that explore different aspects of the new world. And so FFX-2 represents the other, sometimes conflicting tendencies of the RPG boom of the 2000s: a game packed with more and more sidequests, mini-games and content, striving to create a new ur-genre with something for everyone. Yuna’s many ventures include (and are by no means limited to) managing a Blitzball team, practicing a dance routine in a rhythm mini-game, venturing through a dungeon by solving math problems, romantically pairing up monkeys, selling concert tickets, and thwarting a gold-digging cactuar. There’s even a House of the Dead-style shooter where Yuna blasts oncoming Tonberries. Not every sidequest is brilliant, but they don’t have to be. Like any great double-disc rock album, FFX-2’s accomplishments are its scale and diversity, rather than a precise execution of a single idea; FFX-2 is the White Album to FFX’s Abbey Road.

And so the player advances through the two games in opposite ways. Progress in most RPGs can usually be traced as movement through space: traveling through one dungeon and then another, or opening up more of the world map with new vehicles. Final Fantasy X is as good an example as any, with almost the entire game consisting of forward movement along a linear road. But because FFX-2 allows virtually every location to be visited from the get-go, progress in the game is largely defined as movement through time. Completing key plot events shifts the game forward into the next “Chapter,” representing a new development in Spira’s unfolding political crisis. It’s an interesting way for the game to create a sense of progress in a world in which virtually every location can be visited from the beginning. Persona 3 and 4 would take this concept even further, restricting the player to a tiny geographic location but showing its development through a year of seasons, holidays, and life changes.

Here Comes Your Man

No subplot, of course, is more important than the fate of Yuna’s lost love. When Square first announced a sequel to Final Fantasy X, many people correctly guessed it would amend the first game’s uncharacteristically bittersweet ending: Tidus, who was never really anything more than a summon spell, vanishes from Spira, leaving behind a victorious but heartbroken Yuna.

Like many people, I was skeptical about Tidus’ impending resurrection. Wouldn’t that undo the whole point of Tidus’s narrative arc? Wouldn’t that cheapen the ending of the original game? What ultimately flipped my opinion is that Tidus’s original sacrifice is never treated as a storytelling error to be retconned out of memory. Rather than present some convoluted scenario that just so happens to also result in Tidus’s return, the game is honest and forthright about its desire to give Yuna a happy ending. The Fayth, Spira’s minor deities, acknowledge that Yuna has done more for Spira than anyone could expect, and promise to “do what we can” to grant her most fervent wish. And there’s a certain mystery about Tidus’s return–we’re never told the exact metaphysics of how the Fayth brought Tidus back to Spira–that preserves it as a miracle, acknowledged to be outside what should be possible.

Moreover, Tidus’s return is an optional part of the game story, sheltered behind a set of rather convoluted requirements. As our own Andrew Vestal once pointed out, whether Yuna and Tidus are reunited mirrors the player’s own commitment to their relationship. A standard playthrough of the game results in a perfectly satisfying, Tidus-free ending as Yuna embraces her life story and looks ahead to her future. It’s only if the player–and, by extension, Yuna–chases down every last lead about Tidus’s fate that the Fayth determine he should be resurrected. In fact, the biggest flaw in Tidus’s return might be that it’s a little too arcane. For Tidus to return in the ending, the player must whistle for him by mashing a button during a limited window of time during two key cutscenes–without so much as a hint or instruction anywhere. Essentially, it’s an invisible, uncued Quick Time Event. It’s a mechanic only a strategy guide author could love.

In Our Bedrooms After the War

But even though Tidus comes back, the title does an otherwise remarkable job of keeping Spira moving forward. Long-running series set in the same “continuity” have a tendency to devolve into shaggy dog stories in which conflicts stretch on through a parade of sequels without ever finding resolution. Metroid’s ongoing timeline, for instance, seems to consist of Samus discovering yet another colony of “last” Metroids and fighting and re-fighting Ridley for all eternity. And, as GIA alum Jeremy Parish recently noted, the numerous Final Fantasy VII spin-offs seem intent on walking back Cloud’s character development and returning him to his previous sad sack persona.

It’s welcome, then, that FFX-2 allows its characters and world the dignity of changing and developing. Final Fantasy X-2 isn’t about Sin striking back or the old gang getting back together; it’s about permanent, irrevocable change. Yuna and Rikku are still out adventuring, but Wakka and Lulu have settled in Besaid to start a family. The once holy ruins of Zanarkand are now a tourist hotspot, and the old Yevon institutions have given way to a modern nation with factions defined by political ideology: the conservative New Yevon and the revolutionary Youth League. Final Fantasy X-2 starts where most games end–with the Big Bad vanquished–and asks, “Now what?” It’s a more human, more realistic outlook, one that doesn’t rely solely on rampaging monsters for dramatic tension.

Indeed, while Vegnagun might be the final boss, the real story of Final Fantasy X-2 is how Spira copes with rapid change and modernization. Some characters have prospered in the new Spira: The Al Bhed, no longer persecuted by the Yevon church, are doing big business, and the shy monk Shelinda has gained new confidence as a television reporter. But change always has its malcontents, and other characters struggle to find their place. Summoner Isaaru, loyal to Yevon to the end, finds himself demoted to a theme park guide and reminiscing about his glory days. The varied responses to the changes in Spira in many ways presaged fan reaction: Some wanted the old Spira preserved unchanging in amber, some happily jettisoned the past and completely embraced this new vision, and some came to understand both old and new.

Better Version of Me

No one embodies this change more than Yuna. Having grown up expecting to sacrifice her life to save Sin, The Girl Who Lived now struggles to piece together a life she thought never she’d have. More than defusing the threat of Vegnagun, Yuna’s real mission is to find herself: to stand up against the various factions desperate to claim the High Summoner on their side, to define herself as an individual, and to even learn to have a little fun. For Yuna, saving the world has never been a problem; saving herself is the challenge. It’s a far more personal story than FFX, accurately captured by the cheesy slogan on the game’s American packaging: “Last time she saved the world. This time it’s personal.”

The game deserves a great deal of credit for its treatment of Yuna’s quest for self-actualization. When first introduced in FFX, Yuna is almost impossibly self-sacrificing, happy to give her life away to fulfill her duty. The sequel allows her the failings and desires of a real person, making her a more human, more empathetic character without changing her essential nature. She still has a spine of steel when it comes to true moral issues–destroying Sin, resolving Spira’s political crisis–but she’s too kind and generous to say no to her friends’ requests, even when it means wearing a smelly Moogle suit to go undercover. (As one character describes her in-game: “Hero. Summoner. Doormat.”) To be sure, there’s no shortage of do-gooding RPG protagonists ready to throw themselves into minor quests for total strangers, but for once the game actually recognizes that this isn’t always a positive trait; Yuna’s friends tease her and express occasional irritation at being dragged into doing yet another favor for someone. And her most redemptive moment comes when she stumbles across a video of Tidus’s predecessor and doppelganger Shuyin looking for his lost love Lenne, and has a brief fit of jealousy, wondering who this other woman is that Tidus is pursuing. It’s a human moment not allowed of many RPG protagonists. Yuna’s gun-fu theatrics and gangsta pistol grip might be over-the-top silliness, but her emotional journey is never treated with anything but respect.

Yuna’s character is further magnified by the friendship–and excellent characterization–of her two companions. Rikku knows everybody in Spira but fears being left behind when Yuna grows out of adventuring; Paine, tsundere, supplies the muscle. Their camaraderie is greatly strengthened by substantial interaction between Rikku and Paine; they come across as three equal friends, rather than Yuna and her two sidekicks. Yuna’s adventure may be set into motion by a search for her lost love, but her friendship with these two women end up being the core of the game–and play a larger role than in practically any other title. The Last Mission spin-off, available in English for the first time as part of the HD re-release, takes this idea one step further by entirely eliminating world-destroying threats and presenting a story driven purely by the characters’ relationships.

I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times

In late 2001, Grand Theft Auto III exploded past Metal Gear Solid and Final Fantasy to become the “killer app” of the PlayStation 2 generation. The linear, cinematic games that characterized the PSone era gave way to sandbox titles in which the player was largely free to roam the game world, multiple short missions were available at a moment’s notice, and progress was defined less by finishing the main story and more by a percentage counter that tracked whether you’d seen 15%, 72%, or all 100% of what the game had to offer.

While it’s not clear how much direct influence these trends had on Square’s development process, it’s certainly easy to see FFX-2 as the first post-GTA RPG to come out of Japan. Not only could the player wander almost anywhere and, for the first time in Final Fantasy history, undertake explicit “missions,” the game defined progress completely differently. Final Fantasy X-2 tracks what percentage of the game’s story the player has seen, and the very best ending requires not only defeating the main villain, but completing 100% of all the side missions and hidden story scenes. New Game+ makes this task substantially easier by allowing the player to double-count both outcomes of a branching path, but a very thorough–or FAQ-dependent–player can manage it the first time through.

It’s a smart shift. Final Fantasy games have never been particularly challenging, and outside of a few optional boss battles, Final Fantasy X-2 is no exception. For many players, the real goal has always been to discover the game world, max out their characters, and see the whole story. The proliferation of sidequests meant that a player who completed every side story would be drastically overpowered by the end, but a player who took the most direct route would miss out on character and world development. By explicitly separating narrative and gameplay, Final Fantasy X-2 is able to incorporate side missions and hidden story scenes without worrying about their effect on Rikku’s effectiveness in battle.

The odder thing is that this approach didn’t stick. The MMO-influenced Final Fantasy XII greatly downplayed NPCs and complex sidequests in favor of rare drops and monster spawns, as did many of the RPGs that followed in its immediate wake. That’s unfortunate. FFX-2’s structure could have been applied and expanded upon in any number of other RPGs–regardless of their themes and settings–to make exploration and character interaction feel more meaningful.

Always Outnumbered, Never Outgunned

Despite Final Fantasy X-2’s considerable merits, it’s still easy to recognize it as an attempt to assemble a second game out of existing art assets. Many of the new dungeons recycle the same generic textures and geometry, and poor Lulu retains her original character model even while pregnant. FFX-2 was also the first game in the core series to eschew the work of composer Nobuo Uematsu completely, and the resulting soundtrack, while serviceable, falls well short of the series’ usual standards.

But as Final Fantasy X-2 reaches its tenth anniversary and an HD remake looms, it’s slowly emerged from an initial cloud of cynicism to become a title praised, defended, remembered fondly, even held up as a source of inspiration. It’s a long time coming for a game whose initial reception centered primarily on Yuna’s daisy dukes, but it’s well deserved: as a progressively designed RPG with a modern, human story, Final Fantasy X-2 really was a great step forward for Spira.

17 Responses to Final Fantasy X-2: Life is Such a Changing Art

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

What a spirited defense. Both of the FFXs definitely symbolize Square’s impending change into what it is now. It’s nice to remember the good, progressive things they did.

I never did finish FFX-2, just because for all its crazy ideas it never coalesced into anything I could enjoy playing. The highlight was its treatment of Spira as a holistic setting (which was the best part of FFX as well), but every time I tried to dip into that I’d run into the battle system, or the obnoxious characters, or the arbitrary penalties for going places/using features that seemed to be pulled right out of the Sierra point-and-click handbook.

Still, credit to them for trying something big and different.

Excellent article! I can’t wait for the HD versions so I can let myself get absorbed into these games again.

I really enjoyed FFX-2 my first time through, but I would always give up replays a few hours in – and it took me far too long to realize that it was because I kept trying to go for 100% completion. While it can be fun to replay an RPG with a guide open so you can find everything, X-2 is the exception. Following every step towards getting 100% is an exercise in frustration and tedium. I’m excited to play the game the FUN way next time.

Thank you! Yeah, I think the much easier way to get 100% is in New Game+ because you can get extra % points for picking alternate story paths; it’s really a pain to get on one time through. (And the reward for 100% completion is pretty small, anyway–it’s just a short incidental cutscene at the very end.)

Yeah, Spira is definitely the series’ most developed setting and has the strongest sense of “place” (although I think Balamb Garden was pretty good, too).

Yeah, from like FF IV to IX the narrative complexity keep expanded, and they kept adding more side-stuff to do. But by the time of FF X, it’s as though the only way to keep both of those trends was to make two separate games. I feel like both of those trends really contributed to the late ’90s/early ’00s RPG boom, and when they couldn’t be continued, a lot of the appeal of the genre was lost.

And, yeah, it’s easy to see FF X-2 as the precursor to a lot of lame shaggy dog spin-off stories, but it’s hard for me to hold that against the game taken unto itself.

FFX is trash. X-2 is somehow pretty good. I don’t know if it’s more surpring that the game turned out inspired or that I stuck around to figure that out.

“The odder thing is that this approach didn’t stick. The MMO-influenced

Final Fantasy XII greatly downplayed NPCs and complex sidequests in

favor of rare drops and monster spawns, as did many of the RPGs that

followed in its immediate wake.”

The thing that i really dislike about like most of JRPGs nowadays.

Thanks FFXII.

I have to agree that I personally preferred X-2 to X-1 as well although I think that FF X-1 actually executes its vision really well; it’s just that I prefer the more non-linear, less constrained style of X-2 to the polished rollercoaster ride. (And, thematically, X-1 is kind of bleak for me!)

Yeah, I find it a little frustrating that people gripe about side activities like Triple Triad but seem fine with more repetitious activities like “defeat 20 of this monster to finish the quest” or “1/256 chance of this item dropping.” To me, the former style is a lot more interesting! (I can understand why rare drops make sense in an MMORPG economy, but not in a single-player game!)

This really isn’t fair. FFXII had no quests that relied on any of these rare drops or spawns, and they were really only in the game to have a real sense of surprise and discovery when one of the arcane conditions happened to be met. I hate how the game handled chests and a lot of endgame equipment, but they at least made none of it necessary and included a lot of wonderful actual quests.

It also had a much more fleshed-out setting than FFX.

Hmm, Final Fantasy X-2 has a number of qualities that I think sound fine on paper (it has a bunch of sidequests, it’s non-linear, etc), but which are terrible in how they were executed. The game does cheapen FFX’s story by reviving Tidus (frankly, I think he should have been gone, no matter what); it doesn’t matter a lot that actually reviving him is difficult–just knowing that you can revive him cheapens the previous game. I think you mention a number of positive story interpretations of the game, but I don’t particularly care how you spin it–the game’s story is still nauseating. Sure, you get to see Yuna find independence, but you have to suffer through too many wince-inducing cutscenes in the process. Having a bunch of sidequests is fine and all, but I didn’t find any of them in X-2 to be any fun (unlike Triple Triad or Chocobo Hot & Cold), so I could never force myself to get 100% in the game. The potential of the non-linear nature of the game is limited by the game reusing assets from FFX–you don’t get a new world to explore from the get-go; if you’ve played the first game, you’ve already been almost everywhere.

I’m not a terribly big fan of FFX, but I’m certainly less fond of X-2. In retrospect, it’s easy to associate many of Square-Enix’s current failings with X-2 (if I was to point out any point in which the company “sold out,” it’s hard not to point my finger at X-2), although the game itself isn’t really that bad, so it’s entirely unfair to blame the game for later decisions that angered me. And, frankly, while I don’t care for the elements of X-2 that cheapen the ending of FFX, I’m far more upset by how Square-Enix has tarnished FFVII with various sequels (I mean, you can make a case that Yuna benefits from X-2, at least, but Cloud is depicted in sequels as a melancholic wuss that he never quite was in the original game) Regardless, I have no desire to play X-2 again–that much became clear to me when I tried to play a second playthrough in order to obtain a 100% file. The absence of new English voice acting for either Final Fantasy X games has more or less sealed my decision not to buy the HD collection.

My criticism of the FF XII rare drops / rare spawn quests isn’t that they’re required, it’s that they’re *boring*.

The sidequests in other FFs aren’t required, either. But, they were a lot more varied: You’d explore an underwater tower before you ran out of breath, swap rare items in the coliseum, fight through a gauntlet of enemies with just Yuffie, or play a card game. And, they often tied into the characters’ backstories (Shadow’s dreams, Vincent and Lucretia, the Anima summon is Seymour’s mother) or provided some resolution to their subplots (Locke looking for the Phoenix summon to try to revive Rachel).

I feel that FF XII really comes out poorly in a comparison because its optional quests are a lot less interesting than the optional quests in other FFs.

FF XII is my favorite game but not my favorite Final Fantasy. It hardly qualifies! If the series is “about” anything consistent, it’s these character vignettes you point out.

Matsuno’s games are always about a political situation. This includes how it affects people’s ordinary lives, but ultimately his world-building (which is usually giving a perspective on some real-world conflict) is the focus of the story. As a result his characterization is way more subtle. Not better or worse, per se, but approached with an entirely different goal.

This means that side quests are less “LET ME TELL YOU ABOUT MY TRAGIC PAST” and more “this guy in the business district is having problems with a caravan not delivering his goods”. Note that none of these side quests involves getting rare loot or rare monster spawns (the rare game “quest” barely qualifies as such).

So yeah, compared to the classic Peter and the Wolf approach to characterization things look way different, but if you ignore the many quiet and dignified demonstrations of Balthier and Fran’s complicated relationship (to each other and to the political conflict, and the relationship between those relationships) then you’re missing the point of how Matsuno does characters and worlds.

Maybe if Square had decided to ruin Ivalice way sooner FFXII would have been its own game instead of existing awkwardly in a series it has nothing in common with, but so it goes.

You know, after ten years, I still hate this game. I still think of it as the beginning of the end of Final Fantasy, and I still find its structure to be an interminable mess. Compared to more open-ended Western RPGs coming out around the same time like Baldur’s Gate II and Fallout 2, the open nature of the world felt meaningless. There were no dramatic stakes. It felt like the world had turned into a giant theme park. The whole thing felt like a half-thought out, by the seat of its pants, mess.

The part I hated most was Yuna’s speech about how much she regretted all the things she did to save the world in FFX. The whole game seems to be building itself up on a theme of “the past will only weigh you down” and then holds out the reward of Tidus’s resurrection as a teaser.

The mini-games were mostly awful. The new characters were annoying. The entirety of Chapter 4 was misconceived, forcing you to just watch the plot from ground level. It was like a half-cooked experiment devoid of a core focus.

The series never really got back to doing what it did best after Sakaguchi left. The game was a disaster for Final Fantasy. The lack of cohesion of the game was a sign of the eventual lack of a coherent vision for the series as a hole to the point where Bravely Default, the most Final Fantasy looking game in years, isn’t even a Final Fantasy. How’d that happen?

I really enjoyed FFX-2, and I never finished it because despite following the 100% completion guides I’d still inevitably fall short somewhere along the way. That said, in the first game I was one of the few who really REALLY liked Yuna because of that “spine of steel.” When it looked like there was no choice to do something she would screw up her determination and force the rest of the party to find a new way.

I agree very much with your take on her in FFX-2 and for that reason she remains one of my truly favorite FF characters.

I didn’t like it very much but I have to admid that the BS implemented the best ATB system ever.